A personal struggle to maintain idealism in the grip of corporate neoliberal culture.

In my first year as an undergraduate student at the seaside art college of Falmouth University it was instilled in me that designers have an obligation to use their skills for good. We learned about the Bauhaus and modernist utopianism, we worked away at competition briefs for Amnesty International, and explored personal projects on the nature of communication and the importance of sustainability. We were taught that artists, designers and architects were a progressive force — that we could change things if we chose to.

As I made my way into the creative industry, I carried my faithful idealism next to my freshly printed business cards. I came to London with an enthusiasm to create things that could, in some tiny way, make an impact — even if just through being something cool to look at. Branding was a fun and exciting sphere, and my chosen vocation allowed me to get paid for doing my hobby all day.

I managed to maintain some optimism through much of my early career, but it doesn’t take long for youthful exhuberance to be tested right from the gate. The seemingly endless slog of underpaid internships, the paternalistic creative director who thinks he’s teaching you by keeping you at work late, the research project for Big Tobacco that you feel obliged to undertake, the pressure to keep up with a lingering male-dominated “bants-culture” that refuses to die — thus begins a process of disillusionment even within just the first year of work.

It’s a gradual and insidious process of normalisation that makes you forget why you started doing something in the first place, as a hobby you love morphs into a job you tell yourself you love. For a good while, the creative process in itself is enough to excuse the briefs that don’t quite sit right, and as a people-pleaser I, like many designers, became pretty much obsessed with winning the respect of my contemporaries and superiors over most other concerns. But like the fresh sea-air in my lungs, my childish idealism was slowly replaced by a cynical London smog, as it became clear it was about as relevant as those oh-so-considered business cards.

We use design to shape experiences. To influence behaviour and to change perceptions. To create and reinforce relationships between people and entities. If we truly believe in the power of branding and visual communication to influence the way people act, we have a responsibility to choose who and what we use our skills in service of.

There is a collective cognitive dissonance in the psyche of the creative industries. We believe we have the power — through strategy, through careful curation of visual and verbal cues, through painstakingly rationalised concepts — to make or break companies and influence whole sectors. But we also seem to harbour private assertions that it doesn’t really matter. I see it as a kind of industry-wide imposter syndrome: maybe we just make things look nice, and maybe it is all frivolous at the end of the day, and maybe your five year old nephew really could have done it and maybe that’s why your parents don’t understand what it is you do exactly.

But if we have any faith at all in the efficacy of our work, it’s time to take its power seriously.

It’s no surprise that the creative industries make up the second biggest economy in the UK — second only to the financial sector. We are the mouthpiece of the consumer economy that drives the financial sector. We are the grease in capital’s machine, we keep the wheels turning and the engine humming. We are the mantra that tells people everything’s actually fine, even when we all know it is not.

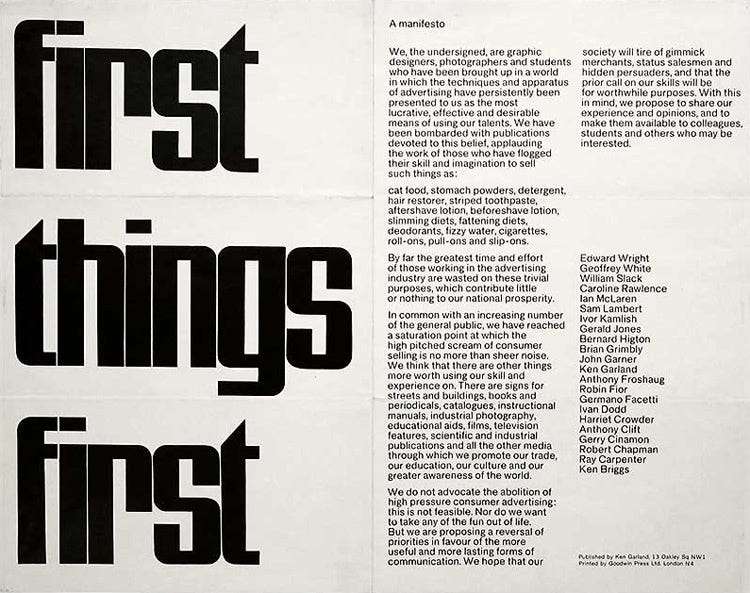

We’ve forgotten that collectively we have agency. When Ken Garland and his co-signers published the First Things First manifesto in 1964, they railed against consumer culture and the “fast pace” and “trivial productions” of advertising (assertions that almost seem laughable relative to today’s output). They advocated for the industry to use its skills in service of education and the betterment of society. Perhaps this was a naive backlash against the inevitable. Or maybe it was a marker of a crucial point when things could have gone differently for society.

Conversely, subsequent generations of designers — now our ECDs and CEOs — would be brought up on the doctrine of neoliberalism and the free market. Nobody had to worry about the moral or social consequences of the work, with the invisible hand waiting in the wings to come in and sort everything out. The pursuit of money was noble in itself — or negated the need to entertain such lofty ideals. Designers and creatives across the world could pour their creative energy into all-nighters and spend the aftermath in the pub, leaving the rest to the divine machinations of the global economy.

But now we know this idea that so absolved us all of responsibility simply wasn’t true. As Naomi Klein documented at the time, the world has undergone a process of privatisation that few had predicted. A process that hoovers up social movements and integrates them into marketing efforts in a performance of consumer progressivism.

It’s become blindingly obvious that “good capitalism” just isn’t really an effective worldview. We need to stop seeing our work, our economies and our societies as seperate entities and start to understand that whatever we choose to do, in our privileged positions as professional designers and creatives, affects everything from our social structures to the environment that birthed them.

We have to start looking for ways to restructure our economies, and we can start with the creative industries. The corporate world, from multinational superbrands to ‘disruptive’ startups, is beholden to the skills of an industry full of people who found a way to monetise our passion — and in doing so often end up losing it. But what if we decided, step by step, client by client, to only service projects we were passionate about? What if we were to actually follow through with the intentions that many of us start out with? This doesn’t have to mean only working for charities and non-profits — it simply means being discerning about our clients’ effect on the world, and asking if we’re happy with amplifying that effect.

The wind is beginning to change. We’ve seen walkouts from developers at Google and Amazon that leave their employers in a tough bind, partly because they need to be seen to be amenable to change, but also because they simply can’t afford to lose the talent. We’ve seen Facebook face an employment crisis as talented would-be recruits no longer seem willing to stomach the effect the company knows it has on the world. Simultaneously, movements like Extinction Rebellion have gained traction in part because of their founders’ experience in marketing and advertising. We can be powerful and we do have agency if we choose to use it.

In the last decade or so working in the branding and graphic design industry, I’ve worked on many different briefs for a range of clients. Like most designers, I’ve relied on my employer to dictate the kind of work that comes across my desk, accepting that the people who pay my wages are the ones that ultimately get to decide what I spend my time doing. But lately I’ve been trying to view my skills as an asset for whoever I choose to use them in service of, and to take these decisions into my own hands.

At this stage in my career I recognise that my position of relative experience means I have more power than I used to. As a junior designer I did not refuse to work on the gambling, payday loans, and shady tax-haven clients that came across my desk, and as a freelancer I found myself dropped in on plenty of queasy briefs — I may have sheepishly expressed unease now and then, but I mainly felt that I didn’t really have a choice. I know it’s much easier said than done. But we should understand that we do have some power, at every level.

I want to encourage graduates and young creatives to be bold enough to express your misgivings about working for unscrupulous clients. Talk to your colleagues about it, talk to your line managers about it. Make a fuss. Know that in this country (for now at least) you can’t be fired for voicing your concerns. And I want to challenge employers to listen to your employees’ concerns, and to seriously consider the ethics of the people you choose to work with. It’s a moral issue, but it’s also increasingly a human resources issue — the next generation of truly talented, conscientious young creatives is not going to be as willing to forgoe corporate ethics.

And if our counterparts at these corporations can no longer work with the progressive, smart, collaborative creative agencies that they enjoy working with, they might have even more reason to think twice about who they work for, until the companies themselves have to reckon with the fact that no-one wants to work for them.

Now is the time to start believing in our own influence as a creative community. It might start small — championing one or two amazing clients, refusing one or two not-so-amazing ones — but in selecting carefully who we are willing to work with we might quickly begin to help shift our culture in the direction that’s so urgently needed in order to make significant change possible. Because branding, marketing, design, advertising — it’s all culture. We need to face up to the fact that what we produce and who we produce it for really does make a difference.

Leave a Reply