On the infantilisation of branding

Another day, another scroll through Brand New while I procrastinate doing my own work by looking at other people’s. On this occasion I was lapping up the new effort from Ragged Edge: a rebrand of an insurance startup that seeks once again to disrupt an industry. As with most of their projects, I was feeling the usual mix of ‘I wish I had done that’ envy and inspiration, until I got about halfway down the page and a different thought came into my head: ‘I’m baby’.

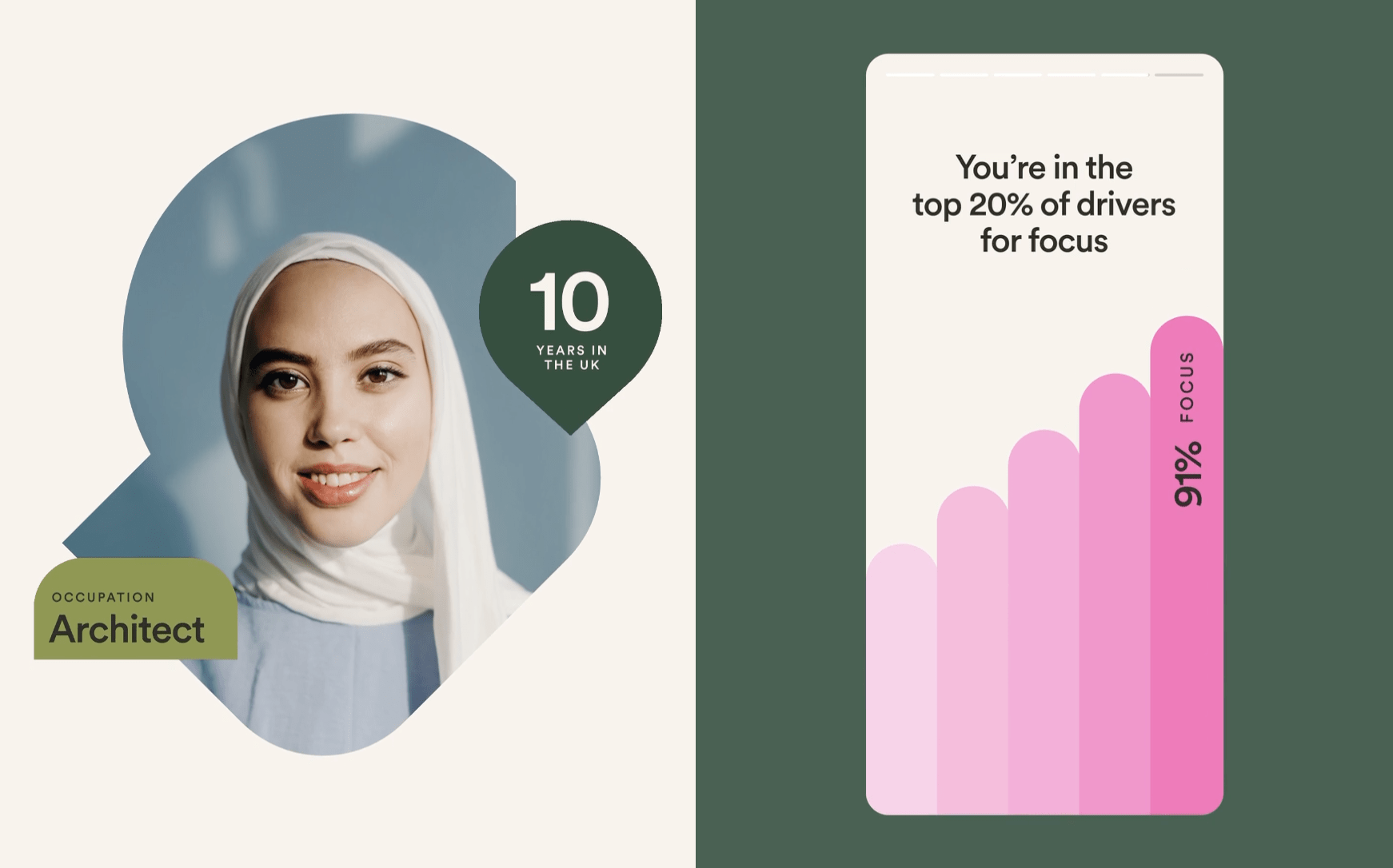

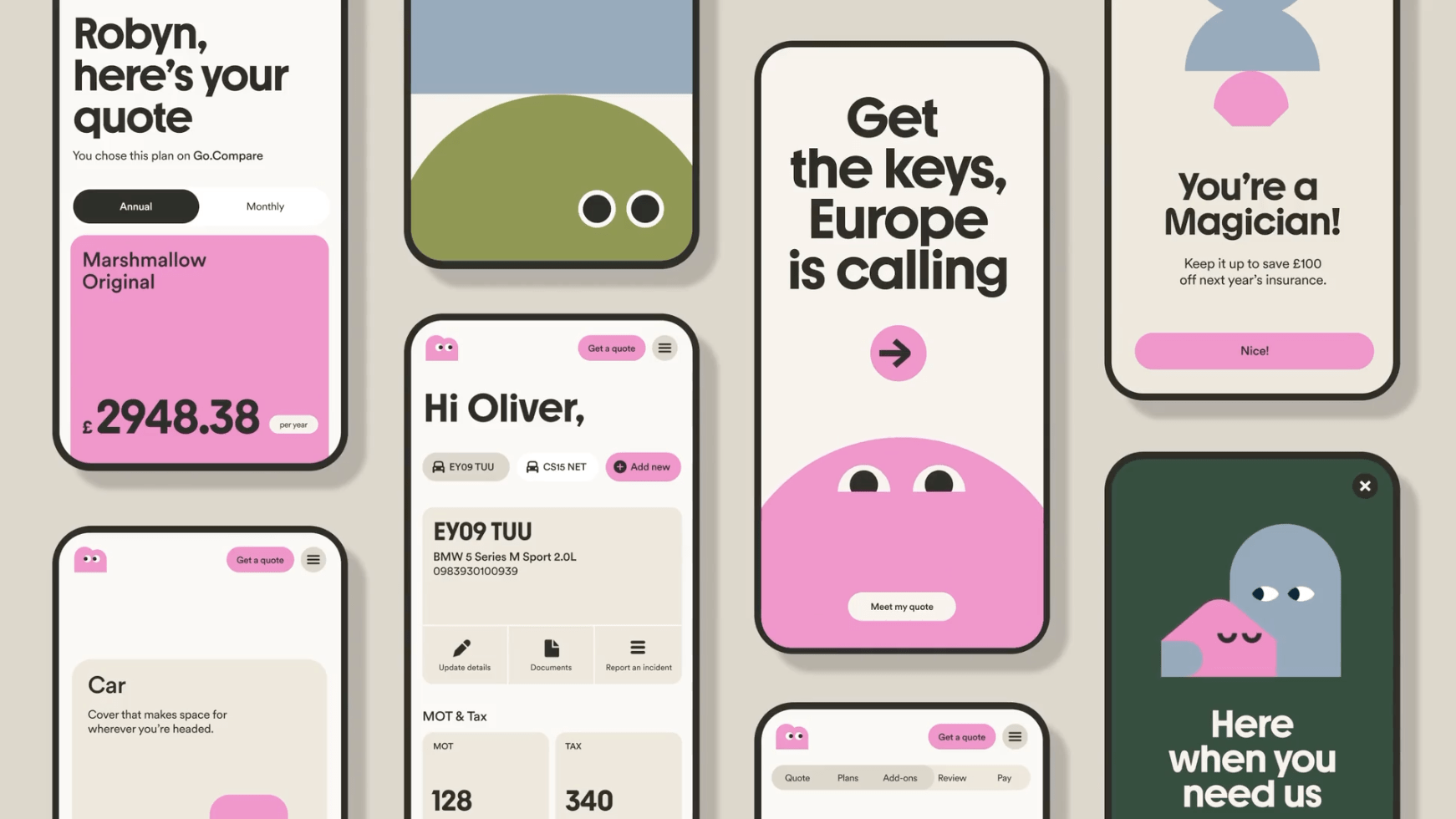

Here I was, 36 years old, nerding out over some design for an insurance company called “Marshmallow” that features at its centre a friendly pink character called Marshall. It’s beautiful work that looks basically indistinguishable from many of the picture books I’ve bought my nieces and nephews in recent years.

From the playschool font to the pastel colours, to the anthropomorphised infographics, if it wasn’t for the subject matter, you’d be forgiven for mistaking this for an early-years education app.

This is not to undermine the work—I’m very much impressed by the consistent quality of Ragged Edge and I’m sure this will be a really effective rebrand—I’m not even trying to say there’s anything wrong with making things cute. It’s fun and I like it. But I think it’s worth thinking about this trend and where it came from, and what it tells us about where we’re at right now.

Adulting is hard

When I think of my generation I think of soaring house prices, expensive coffees and 50 hour work weeks. I’m part of a certain section of society that’s low on time and owns little in the way of actual wealth, but has enough disposable income to spend on door-to-door deliveries, brunches and meal kits. The intersection of my generation and class is one in which we’ve gotten used to having things done for us. Apps now seek to take the place of our parents: Deliveroo for lunch, Uber home, Hello Fresh for dinner. Monzo makes me feel like it’s managing my finances for me, and, when last year I was finally able to buy a flat, Habito took care of the mortgage.

All of this seems to make life easier, and I barely have to even (god forbid) speak to a person on the phone. It’s no wonder then, that the world of branded apps and financial services feels like a playground filled with brightly coloured friendly characters and squishy anthropomorphic shapes.

Sometimes this represents genuine technological improvement: think of the experience of banking now compared to 20 years ago and it’s hard to deny that the service is much better than it used to be.

But I’m also left with the uncanny feeling of being fooled into a false sense of security. A state of mind that is passive, trusting and pliable, filled with long-underused subscription services that I’ll sort out tomorrow I swear.

On a collective level I think this leads to a general tendency towards stasis. Things may have got considerably worse for our generation materially, and everything is much more expensive than it used to be, from the cost of a pint of lager to higher education, but everything feels so easy now that maybe it’s actually fine. And that’s of course overlooking the human cost of this perceived ease—the precarious gig-work that actually makes these apps work, from UberEats riders to freelance mortgage brokers and therapists, each sector becoming one-by-one more ruthless and ‘disrupted’ from the bottom up.

Early in my career I was fortunate enough to spend a 3-month stint working in the Google offices in London. They had a room full of nap-pods, free breakfast, lunch and dinner (with multiple gourmet options), mini-kitchens full of snacks and Mountain Dew, ‘playrooms’ with every latest console and ping-pong and pool tables. It was like going to that one kid’s house who was allowed fizzy drinks and had all the channels and an ADSL line (#just90sthings). The thing is, no-one at Google was using the fun stuff. Most people working there were chained to their screens for so long they had to use the in-house laundry service to get their washing done (and judging by the smell on the coding floor, often not making enough use of this service).

I think this might be a good analogy for the app-world that many of us live in now. A generation now in their 30s, stuck in suspended animation as teenagers/young adults, having our needs tended to by more and more services in exchange for degradation in material living- and working-conditions.

Branding has a big role to play to make this world palatable. It’s the tool that the libertarian tech industry uses to make us feel safe, looked-after, coddled. Like story-books, these brands want to make this increasingly privatised, individualised economy feel like a fun adventure, and it seems like the worse the economy gets, the more infantilising these stories become.

Finding job-hunting alienating, depressing and unmotivating? Actually, it’s fun, like making pretend you’re in a jungle 🙂

Getting nothing from your savings? Stick it all into crypto! It’s fun and quirky and definitely not a pyramid scheme 🙃

I always try to make these rants productive, and where I can find productivity here is in learning from the best how to make things like climate action and social justice more palatable to more people (if it can be done with insurance, maybe there’s something to learn there).

On the flip side I think there’s an appetite out there for audiences and citizens to be treated, and marketed to, like adults. There’s got to be a sweet spot in between treating audiences with seriousness and respect, and providing citizens with fun and accessible (and yes, even cute) experiences. I think that might be a good thing to aim for.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this, consider subscribing and/or sharing 🙂

It’s paywalled, but I recommend watching Brad Troemel’s Pastel Hell Report that covers how we got to this millennial tendency to infantilise ourselves.

Podcast highlight:

Sticking to the millennial theme (and to the Replyall adjacent theme from last week), I just discovered PJ Vogt’s new podcast, and enjoyed this ep on music discovery titled ‘How do I find new music now that I’m old and irrelevant?’. I find myself having the same ridiculous neuroses as PJ when it comes to finding music in the “right” places, and judging what’s actually good vs what’s just catchy (and if there’s any difference!)

Leave a Reply