A few things I’ve learned.

I’ve long felt that charity and cause campaigning often takes the wrong approach, leading with problems over solutions, highlighting symptoms above root causes. It’s understandable, when the consequences of climate collapse, famine and injustice are so shocking, to want to show the world—to shine a spotlight on the awful thing. But I think this approach is limiting.

It’s been a while since Bob Geldof and co originally attempted to save the world through a combination of music and horror, and it’s now becoming more widely understood that leading with the problem—showing people in the bleakest of situations—leads to what Adam Curtis terms “oh-dearism.” This is the feeling of anguish, of a problem’s perceived unsolvability—the sheer desperation of it all—that may hammer home the importance of doing something, but ironically does not inspire a person to do anything, and worse, can rob people on the ground of their own agency.

Having worked with many charities and organisations, large and small, to help connect with their audience through design, I thought I’d outline a couple of things I’ve learned along the way.

Selling solidarity

The traditional approach to international aid has been to highlight the effects of catastrophe, and to almost guilt people into handing over their money. As I mentioned up-top, this may work in the short-term, but after decades of this strategy, it’s likely to have an apathy-inducing effect on the public.

But arguably what’s more important is the imbalance this causes in the perceived relationship between “us” in the West and “them” in what we call the Global South. We need to start approaching aid from the position of solidarity over charity, and this has become central to how I see communication in this sector.

It’s also something that Oxfam wanted to address in redesigning the Unwrapped range of gift cards. We made a big decision to take photographs of people off the covers of the cards, and instead illustrate the Oxfam programmes that are funded by the cards in a positive and celebratory way, that centres on the outcomes. We also wanted to highlight the partnerships Oxfam has built with people on the ground, making it clear that Oxfam are participants in this work alongside the communities themselves.

The aim here is to build a sense of solidarity between the person purchasing the card, the person receiving the card, and the Oxfam partner whose project benefits from the transaction.

This is what is meant by decolonisation—fundamentally shifting our mindset from the idea that ‘developed’ nations can benevolently lift those they deem sufficiently worthy out of poverty, to the shared understanding of the global systems that put them there in the first place, and that allow some humans to live in comfort while others live in desperation.

Tasty bites:

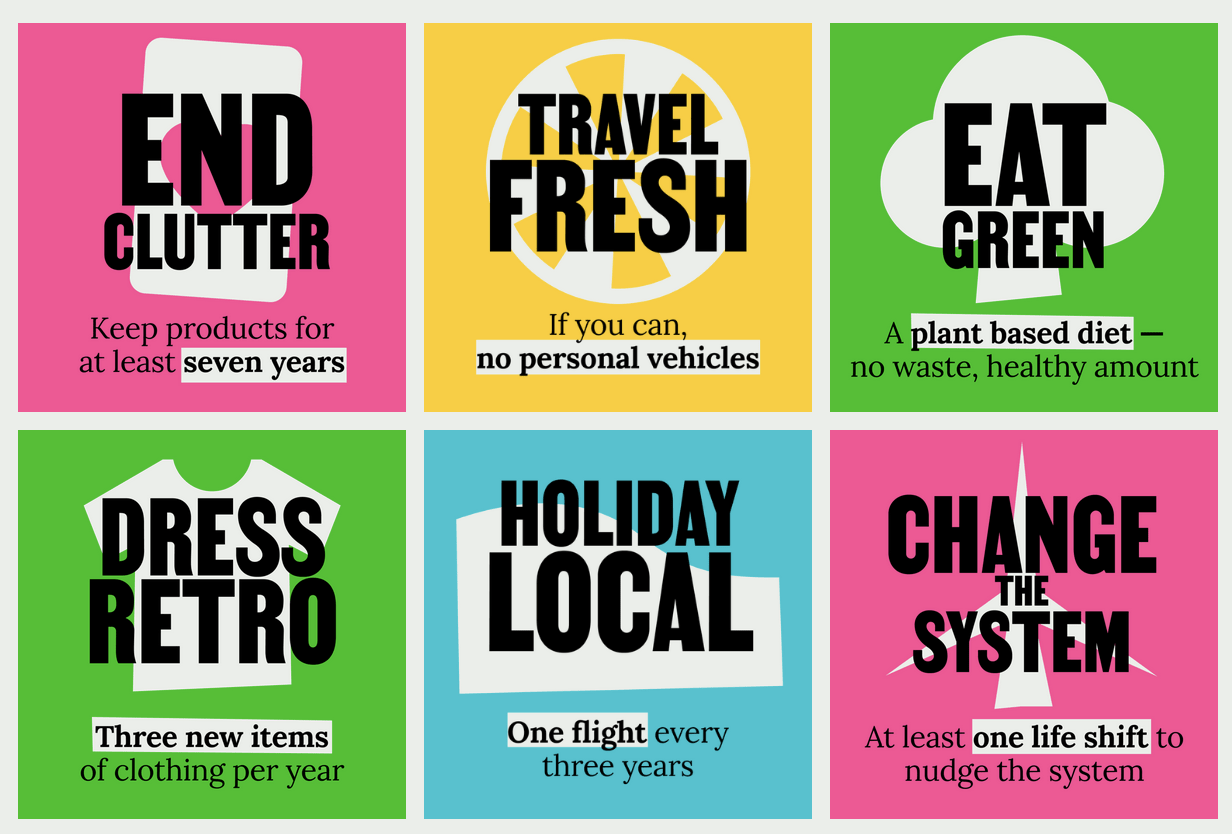

If you’re trying to inspire action, it’s important that action feels doable, or even better, enjoyable. Take the Jump encourages people with the means to do so to take part in six, manageable lifestyle changes.

Crucially they acknowledge the difficulty of making even a small lifestyle change, and focus on celebrating the increments, rather than admonishing failures. Their whole approach is centred on joy, community and celebration, and it was super-important that their brand toolkit allowed them to communicate those things.

This was a valuable lesson for me in creating a brand for use by volunteers with varying levels of design-literacy. Based on the use of a distinctive typeface, cut-out shapes and a bold, bright colour palette, the brand benefits from being thrown together in an exuberant way.

Space for Empathy

Creating a positive experience encourages people to build an emotional connection to a subject. This is something that the retail sector has long been aware of: just look at Glossier, Aesop, Apple and any flagship Nike store for just a few examples.

When we created the Choose Love stores we wanted to use the psychology and techniques of the retail sector to essentially solicit donations for refugees. By creating an experience that people felt drawn to, with moments of surprise, delight and storytelling, people’s empathy was allowed to naturally come out. We were struck by the power of objects to elicit an emotional response, with many people brought to tears by the touch of a child’s coat or boot.

The responses may have been emotional, but the experience itself was overwhelmingly positive—a celebration of the amazing work that Choose Love enables across the world.

Branding and design can create a positive, celebratory space in which to communicate serious, important issues. This space can be physical or digital—it’s the amalgamation of the experience created in the audience’s mind—and it can even start to change our whole culture.

Thanks for reading Design in Progress!

While I’m new to this, I’m enjoying the process of writing about communication, culture and the climate crisis.

If you’ve found this at all interesting or insightful, please consider sharing with your network!

I don’t plan on charging anyone for this content, but you can subscribe for free below to receive new posts and show your support 🙂

Leave a Reply